3733

Toward 3D Printed, Anatomy-Mimicking, Quantitative MRI Phantoms1Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, United States

Synopsis

We aim to design and build reproducible phantoms with anatomy-mimicking resolution and image contrast. We mix solutions of paramagnetic ions in agar gel to target specific relaxation parameters. Chambers for different tissue types are 3D printed and filled with the agar gels. Microfiber cloths are added to create additional high-resolution structure. We validate the ability to reproduce target relaxation values through spin-echo imaging and quantitative mapping, and present two 3D printed phantom designs.

Introduction

Quantitative MRI methods aim to estimate tissue parameters from one or several scans. Typically, these methods are first validated using phantoms containing separate vials of chemically-doped aqueous solutions mimicking different tissue T1, T2, spin-density, and diffusion coefficients$$$^{1}$$$. Although these system phantoms act as a good first-pass test, they often lack the complicated structure and resolution seen in real anatomy$$$^{2-4}$$$. The importance of fine structure and realistic contrast is especially critical for validating advanced quantitative methods that rely on spatio-temporal modeling, e.g. through compressed sensing$$$^{5}$$$, MR Fingerprinting$$$^{6}$$$, and partial separability$$$^{7}$$$. In this work we aim to build a quantitative MR phantom with anatomy-mimicking fine structure that can be created with basic chemicals and a 3D printer. Our approach was inspired by and leverages the open source MGH phantom project$$$^{8}$$$. We achieve a broad range of T1 and T2 parameters by varying mixtures of nickel chloride (NiCl2), manganese chloride (MnCl2), and agar gel, and demonstrate the flexibility in combining the gels with 3D-printed structures.Materials and Methods

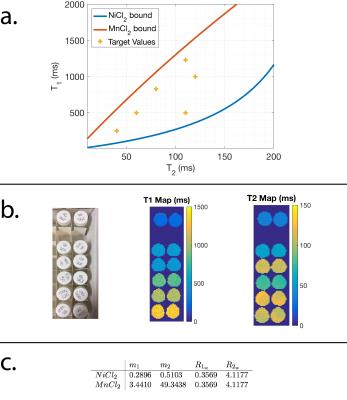

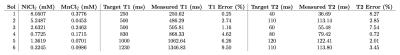

We prepared 20 mL vials containing 0.15 g agar, 0.1 g NaCl, and varying concentrations of chemically-doped water with either NiCl2 or MnCl2 using serial dilution$$$^{9,10}$$$. The vials were heated on a hot plate and periodically mixed using a vortex mixer to form a uniform solution of agar gel. The vials were scanned on a Siemens 3T Trio scanner using spin-echo and inversion recovery at different echo and inversion times (TR: 4000 ms, TE: 10,25,50,75,120 ms, TI: 100,500,900,1300,2000 ms, 12 channels). From the scans, R1=1/T1 and R2=1/T2 values were estimated$$$^{11}$$$ and the concentrations of chemicals were fit to the linear relationships$$$^{9}$$$: $$R1=m_{1a}k_a+m_{1b}k_b+R1_w$$$$R2=m_{2a}k_a+m_{2b}k_b+R2_w,$$where R1 and R2 are the measured relaxation and $$$k_a$$$ and $$$k_b$$$ respectively are the known concentrations of NiCl2 and MnCl2 in millimolar. The slopes ($$$m_{1a},m_{1b},m_{2a},m_{2b}$$$) represent the change in relaxation as a function of the concentration of each chemical, and the intercepts ($$$R1_w,R2_w$$$) are the expected relaxation constants of the agar gel in the absence of any chemical. Following the linear fit, we find the range of (T1,T2) pairs that are achievable by mixing NiCl2 and MnCl2 together into a single solution$$$^{9}$$$. Solutions were prepared containing mixtures of both chemicals to target specific relaxation pairs, and these solutions were mapped with the spin-echo protocol. To re-calibrate the linear fit, the measured relaxation rates along with the known concentrations were used to re-derive the slopes and intercepts. After validating the feasibility of targeting specific relaxation values, larger quantities of the gels were prepared. A 3D-printed polylactic acid (PLA) brain shell containing chambers for cerebrospinal fluid (filled with water), white matter, and gray matter was built. Each chamber was manually filled with a gel mixture as it was printed. To add additional high-resolution structure, micro-fiber cloths (as suggested by private correspondence with Dr. Larry Wald, Harvard MGH) were saturated with the gel and submerged in the brain shell. The final 3D-printed brain was scanned to validate the relaxation values.Results

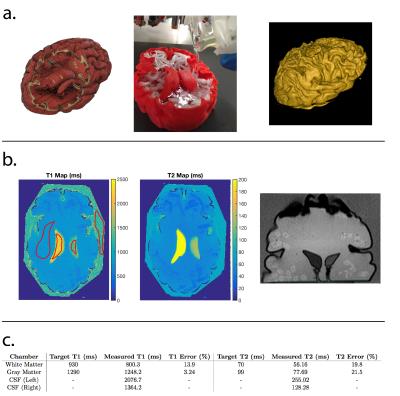

Figure 1 shows a photo of the vials each containing a single chemical, and the (T1,T2) maps and the linear fits derived from the data. Based on the linear fits, the range of feasible (T1,T2) pairs was calculated, and solutions containing both chemicals were prepared to target specific relaxation pairs. The target (T1,T2) values are shown in Figure 2, as well as a photo of the vials containing both chemicals and the relaxation maps derived from the scans. The error between the target and measured relaxation values for each solution are shown in Figure 3 and was less than 9%. Figure 4 shows the design and construction of the 3D-printed brain shell, which was placed in a laser-cut acrylic box, as well as MR images and the estimated relaxation maps. The errors between the target white matter and gray matter ROIs are shown in Figure 4c. Figure 5 shows a similar design, construction, and imaging result for a phantom containing arbitrary shapes with chambers for different chemical concentrations.Discussion

The ability to target specific relaxation values depends largely on the repeatability of the gel fabrication. When preparing large quantities of the gels (above 150 mL), we found better reproducibility through heating in a microwave and periodically stirring. Difficulty remains in eliminating air bubbles, and the process may necessitate an oxygen-isolated environment. Future work will investigate the effect of varying the amount of agar gel as well as establishing protocols for building reproducible phantoms that can be distributed to the community.Conclusion

Quantitative phantoms with tissue-mimicking contrast and structure are feasible through a combination of chemically-doped agar gel and 3D-printed compartments.Acknowledgements

We thank the UC Berkeley Brain Imaging Center for use of their facilities and the MGH Martinos Center for making plans and 3D printing instructions freely available online.References

1. Russek SE, Boss M, Jackson EF, Jennings DL, Evelhoch JL, Gunter JL, Sorensen G. Characterization of NIST/ISMRM MRI System Phantom. In Proceedings of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, Vol. 22, Melbourne, Australia, 2012. pp. 2456.

2. Kasten JA, Vetterli T, Lazeyras F, Van De Ville D. 3D-printed Shepp-Logan Phantom As a Real-world Benchmark for MRI. Magnetic resonance in medicine 75, no. 1 (2016): doi:10.1002/mrm.25593

3. McElcheran C, Yang B, Tam F, Golenstani-Rad L, Graham S. Heterogeneous gelatin-based head phantom for evaluating DBS heating. In Proceedings of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, Vol. 24, Singapore, 2016. pp. 2222.

4. Deniz C, Chang G, Brown R. 3D printed phantom for optimization of trabecular bone structure imaging. In Proceedings of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, Vol. 24, Singapore, 2016. pp. 2289.

5. Doneva M, Börnert P, Eggers H, Stehning C, Sénégas J, Mertins A. Compressed Sensing Reconstruction for Magnetic Resonance Parameter Mapping. Magnetic resonance in medicine 64, no. 4 (2010): doi:10.1002/mrm.22483.

6. Dan M, Gulani V, Seiberlich N, Liu K, Sunshine JL, Duerk JL, Griswold MA. Magnetic Resonance Fingerprinting. Nature 495, no. 7440 (2013): doi:10.1038/nature11971

7. Zhao B, Haldar JP, Christodoulou AG, Liang ZP. Image Reconstruction From Highly Undersampled (k, T)-space Data with Joint Partial Separability and Sparsity Constraints. IEEE transactions on medical imaging 31, no. 9 (2012): doi:10.1109/TMI.2012.2203921.

8. A.A. Martinos Center / Wald group anthropomorphic phantom builder's Wiki. https://phantoms.martinos.org/Main_Page

9. SchneidersNJ. Solutions of Two Paramagnetic Ions for Use in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Phantoms. Medical Physics 15, no. 1 (1988): doi:10.1118/1.596155

10. Mitchell MD, Kundel HD, Axel L, Joseph PM. Agarose As a Tissue Equivalent Phantom Material for NMR Imaging. Magnetic resonance imaging 4, no. 3 (1986): 263-6.

11. Barral, JK, Gudmundson E, Stikov N, Etezadi-Amoli M, Stoica P, Nishimura DG. A Robust Methodology for in Vivo T1 Mapping. Magnetic resonance in medicine 64, no. 4 (2010). doi:10.1002/mrm.22497.

Figures