Chapter

1: Introduction to Embedded Systems

Jonathan Valvano and Ramesh Yerraballi

This chapter covers the basic foundation concepts needed to build upon in this course. Specifically we will look at embedded systems, number representation, digital logic, embedded system components, and computer architecture: the Central Processing Unit (Arithmetic Logic Unit, Control Unit and Registers), the memory and the Instruction Set Architecture (ISA).

Table of Contents:

- 1.1. Embedded Systems

- 1.2. Binary Information Implemented with MOS transistors

- 1.3.

Numbers

- 1.4. Introduction to Computers

- 1.5.

I/O Ports

- 1.6.

Memory

- 1.7.

Instruction Set Architecture

- 1.8.

Designing a NOT gate using a LaunchPad

Video 1.0. Introduction, Examples of Embedded Systems

Reference material relative to this chapter:

- Digital logic

- Assembly reference

- Embedded Software in C for an ARM Cortex M

- TM4C123 LaunchPad Users Manual

1.1. Embedded Systems

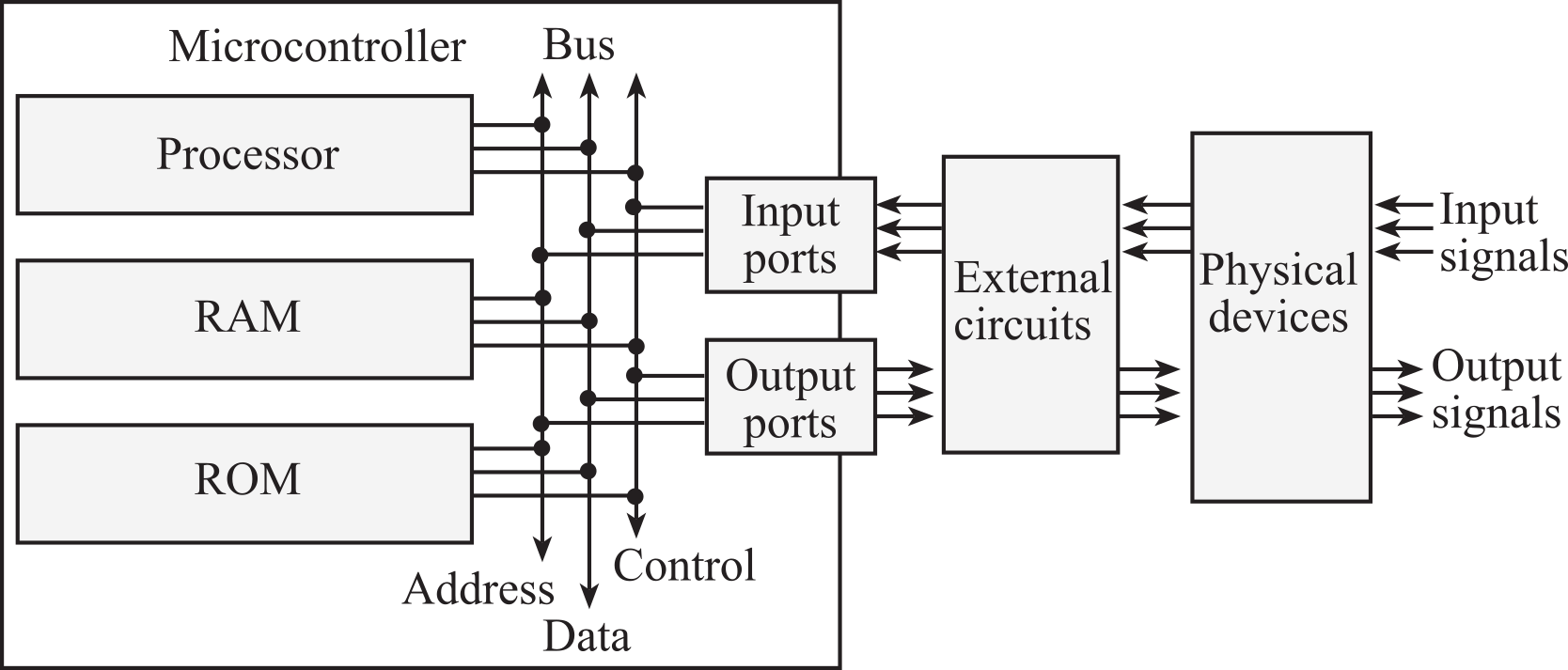

To better understand the expression embedded microcomputer system, consider each word separately. In this context, the word “embedded” means hidden inside so one can’t see it. The term “micro” means small, and a “computer” contains a processor, memory, and a means to exchange data with the external world. The word “system” means multiple components interfaced together for a common purpose. Systems have structure, behavior, and interconnectivity operating in a framework bound by rules and regulations. Another name for embedded systems is Cyber-Physical Systems, introduced in 2006 by Helen Gill of the National Science Foundation, because these systems combine the intelligence of a computer with the physical objects of our world. As shown in Figure 1.1.1, the term embedded microcomputer system refers to a device that contains one or more microcomputers inside. Microcontrollers, which are complete computers incorporating the processor, RAM, ROM and I/O ports into a single package, are often employed in an embedded system because of their low cost, small size, and low power requirements.

Figure 1.1.1. An embedded system includes a microcomputer interfaced to external physical devices.

An embedded system includes a microcomputer with mechanical, chemical, and electrical devices attached to it, programmed for a specific dedicated purpose, and packaged up as a complete system. Any electrical, mechanical, or chemical system that involves inputs, decisions, calculations, analyses, and outputs is a candidate for implementation as an embedded system. Electrical, mechanical, and chemical sensors collect information. Electronic interfaces convert the sensor signals into a form acceptable for the microcomputer. For example, a tachometer is a sensor that measures the revolutions per second of a rotating shaft. Microcomputer software performs the necessary decisions, calculations, and analyses. Additional interface electronics convert the microcomputer outputs into the necessary form. Actuators can be used to create mechanical or chemical outputs. For example, an electrical motor converts electrical power into mechanical power.

If the embedded system is connected to the

internet, it is classified as an Internet of Things (IoT).

Video

1.1.1. Components of an embedded system

Figure 1.1.2. Embedded systems have computers hidden inside.

: What is an embedded system?

1.2. Binary Information Implemented with MOS transistors

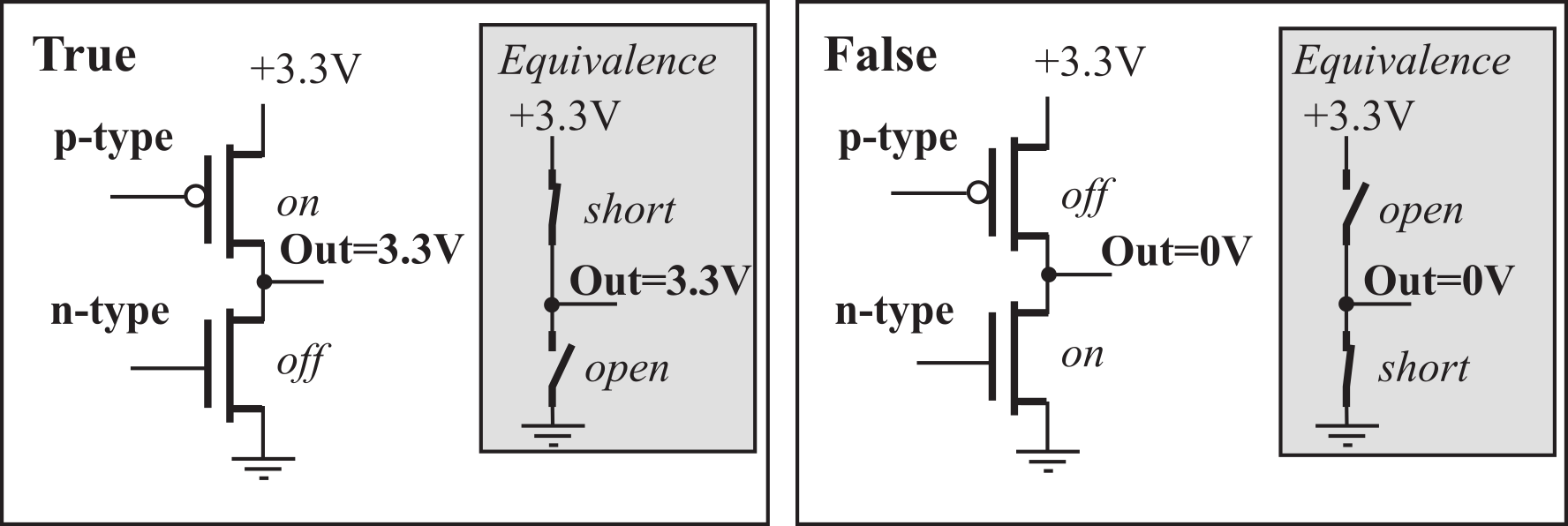

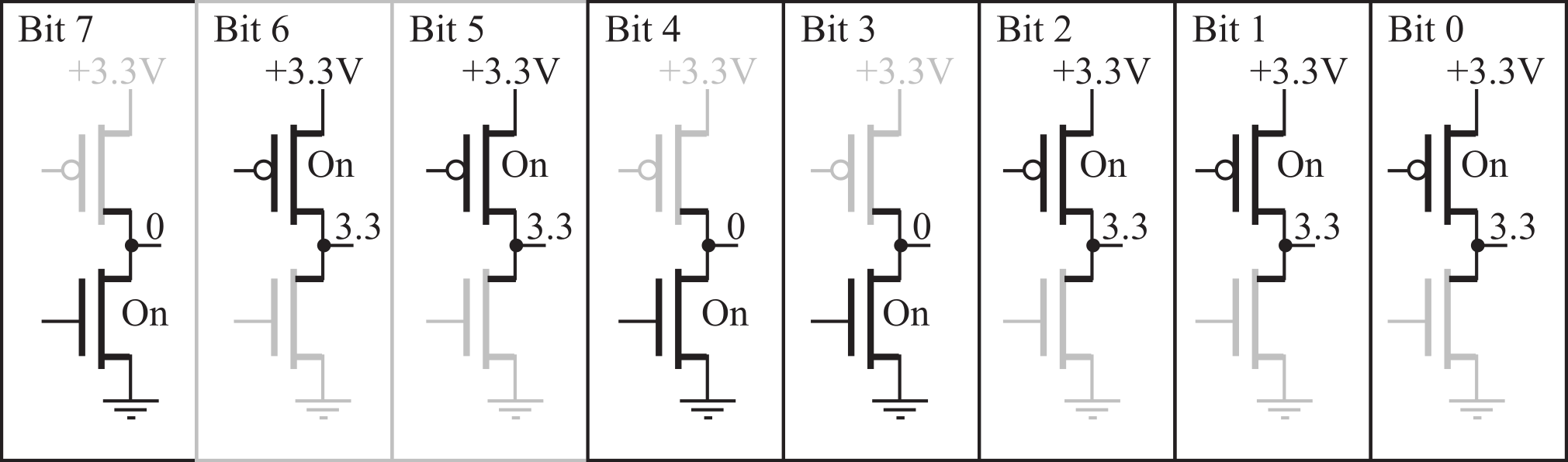

Information is stored on the computer in binary form. A binary bit can exist in one of two possible states. In positive logic, the higher voltage is called the ‘1’, true, asserted, or high state. The lower voltage is called the ‘0’, false, not asserted, or low state. Figure 1.2.1 shows the output of a typical complementary metal oxide semiconductor (CMOS) circuit. The left side shows the condition with a true bit at the output, and the right side shows a false at the output. The output of each digital circuit consists of a p-type MOS transistor “on top of” an n-type MOS transistor. In digital circuits, each transistor is either on or off. If the transistor is on, it is equivalent to a short circuit between its two output pins. Conversely, if the transistor is off, it is equivalent to an open circuit between its outputs pins.

Figure 1.2.1. A binary bit at the output is true if a voltage is present and false if the voltage is 0.

: What would have if both transistors were on in Figure 1.2.1?

: What would have if both transistors were off in Figure 1.2.1?

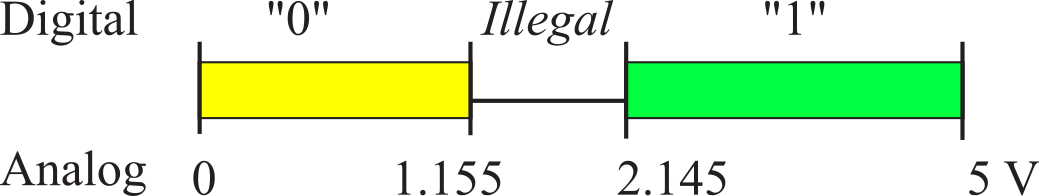

Every family of digital logic is different, but on the TM4C microcontrollers from TI powered with 3.3 V supply, a voltage between 2.145 and 5 V is considered high. In general we define VIH as smallest input voltage considered high. A voltage between 0 and 1.155 V is considered low, as drawn in Figure 1.2.2. In general we define VIL as largest input voltage considered high. Separating the two regions by 0.99 V allows digital logic to operate reliably at very high speeds. The design of transistor-level digital circuits is beyond the scope of this book. However, it is important to know that digital data exist as binary bits and encoded as high and low voltages.

Figure 1.2.2. Mapping between analog voltage and the corresponding digital meaning on the TM4C.

If the information we wish to store exists in more than two states, we use multiple bits. A collection of 2 bits has 4 possible states (00, 01, 10, and 11). A collection of 3 bits has 8 possible states (000, 001, 010, 011, 100, 101, 110, and 111). In general, a collection of n bits has 2n states. For example, a byte contains eight bits and is built by grouping eight binary bits into one object, as shown in Figure 1.2.3. Another name for a collection of eight bits is octet (octo is Latin and Greek meaning 8.) Information can take many forms, e.g., numbers, logical states, text, instructions, sounds, or images. What the bits mean depends on how the information is organized and more importantly how it is used. This figure shows one byte in the state representing the binary number 01100111, which could mean 103. As a character, this same collection of bits represents the letter ‘g’. Again, the output voltage 3.3V means true or 1, and the output voltage of 0V means false or 0.

Figure 1.2.3. A byte is comprised of 8 bits, in this case representing the binary number 01100111.

: Why is there a gap between VIL and VIH?

: The TM4C123 is powered at 3.3V. Can you think of a reason to reduce the supply voltage to 1.65V?

1.3. Numbers

A great deal of confusion exists over the abbreviations we use for large numbers. In 1998 the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) defined a new set of abbreviations for the powers of 2, as shown in Table 1.3.1. These new terms are endorsed by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) and International Committee for Weights and Measures (CIPM) in situations where the use of a binary prefix is appropriate. The confusion arises over the fact that the mainstream computer industry, such as Microsoft, Apple, and Dell, continues to use the old terminology. According to the companies that market to consumers, a 1 GHz is 1,000,000,000 Hz but 1 Gbyte of memory is 1,073,741,824 bytes. The correct terminology is to use the SI-decimal abbreviations to represent powers of 10, and the IEC-binary abbreviations to represent powers of 2. The scientific meaning of 2 kilovolts is 2000 volts, but 2 kibibytes is the proper way to specify 2048 bytes. The term kibibyte is a contraction of kilo binary byte and is a unit of information or computer storage, abbreviated KiB.

1 KiB = 210 bytes = 1024 bytes

1 MiB = 220 bytes = 1,048,576 bytes

1 GiB = 230 bytes = 1,073,741,824 bytes

These abbreviations can also be used to specify the number of binary bits. The term kibibit is a contraction of kilo binary bit, and is a unit of information or computer storage, abbreviated Kibit.

A mebibyte (1 MiB is 1,048,576 bytes) is approximately equal to a megabyte (1 MB is 1,000,000 bytes), but mistaking the two has nonetheless led to confusion and even legal disputes. In the engineering community, it is appropriate to use terms that have a clear and unambiguous meaning.

|

Value |

SI Decimal |

SI Decimal |

|

Value |

IEC Binary |

IEC Binary |

|

10001 |

k |

kilo- |

|

10241 |

Ki |

kibi- |

|

10002 |

M |

mega- |

|

10242 |

Mi |

mebi- |

|

10003 |

G |

giga- |

|

10243 |

Gi |

gibi- |

|

10004 |

T |

tera- |

|

10244 |

Ti |

tebi- |

|

10005 |

P |

peta- |

|

10245 |

Pi |

pebi- |

|

10006 |

E |

exa- |

|

10246 |

Ei |

exbi- |

|

10007 |

Z |

zetta- |

|

10247 |

Zi |

zebi- |

|

10008 |

Y |

yotta- |

|

10248 |

Yi |

yobi- |

Table 1.3.1. Common abbreviations for large numbers.

To solve problems using a computer we need to understand numbers and what they mean. Each digit in a decimal number has a place and a value. The place is a power of 10 and the value is selected from the set {0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9}. A decimal number is simply a combination of its digits multiplied by powers of 10. For example

1984 = 1•103 + 9•102 + 8•101 + 4•100

Fractional values can be represented by using the negative powers of 10. For example,

273.15 = 2•102 + 7•101 + 3•100 + 1•10-1 + 5•10-2

In a similar manner, each digit in a binary number has a place and a value. In binary numbers, the place is a power of 2, and the value is selected from the set {0, 1}. A binary number is simply a combination of its digits multiplied by powers of 2. To eliminate confusion between decimal numbers and binary numbers, we will put a subscript 2 after the number to mean binary. Because of the way the microcontroller operates, most of the binary numbers in this class will have 8, 16, or 32 bits. An 8-bit number is called a byte, and a 16-bit number is called a halfword. For example, the 8-bit binary number for 106 is

011010102 = 0•27 + 1•26 + 1•25 + 0•24 + 1•23 + 0•22 + 1•21 + 0•20 = 64+32+8+2 = 106

: What is the numerical value of the 8-bit binary number 111111112?

Video 1.3.1. Binary representation

You have already learned how to convert from a binary number to its decimal representation. All you need to do is to calculate its value by multiplying each coefficient by its placeholder values and summing all of them together. If you want to practice, first think of an 8-digit binary number, and next type into the box from 1 to 8 binary digits. Try to calculate the decimal representation in your head. Then click "convert" to check your result.

Binary is the natural language of computers but a big nuisance for us humans. To simplify working with binary numbers, humans use a related number system called hexadecimal, which uses base 16. Just like decimal and binary, each hexadecimal digit has a place and a value. In this case, the place is a power of 16 and the value is selected from the set {0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, A, B, C, D, E, F}. As you can see, hexadecimal numbers have more possibilities for their digits than are available in the decimal format; so, we add the letters A through F, as shown in Table 1.3.2. Hexadecimal representation is a convenient mechanism for us humans to define binary information, because it is extremely simple for humans to convert back and forth between binary and hexadecimal.

Video 1.3.2. Hexadecimal representation

|

Hex Digit |

Decimal Value |

Binary Value |

|

0 |

0 |

0000 |

|

1 |

1 |

0001 |

|

2 |

2 |

0010 |

|

3 |

3 |

0011 |

|

4 |

4 |

0100 |

|

5 |

5 |

0101 |

|

6 |

6 |

0110 |

|

7 |

7 |

0111 |

|

8 |

8 |

1000 |

|

9 |

9 |

1001 |

|

A or a |

10 |

1010 |

|

B or b |

11 |

1011 |

|

C or c |

12 |

1100 |

|

D or d |

13 |

1101 |

|

E or e |

14 |

1110 |

|

F or f |

15 |

1111 |

Table 1.3.2. Definition of hexadecimal representation.

For example, the hexadecimal number for the 16-bit binary 0001 0010 1010 1101 is

0x12AD = 1•163 + 2•162 + 10•161 + 13•160 = 4096+512+160+13 = 4781

You have already learned how to convert from a hexadecimal number to its decimal representation. All you need to do is to calculate its value by multiplying each coefficient by its placeholder values and summing all of them together. If you want to practice, Choose an 4-digit hexadecimal number number. Try to calculate the decimal representation. Then type the number in the following field and click "convert" to check your result.

: What is the numerical value of the 8-bit hexadecimal number 0xFF?

: Convert the binary number 010001012 to hexadecimal.

: Convert the binary number 1100101010112 to hexadecimal.

: Convert the hex number 0x40 to binary.

: Convert the hex number 0x63F to binary.

: How many binary bits does it take to represent 0x123456?

Precision is the number of distinct or different values. We express precision in alternatives, decimal digits, bytes, or binary bits. Alternatives are defined as the total number of possibilities. For example, an 8-bit number format can represent 256 different numbers. An 8-bit digital to analog converter (DAC) can generate 256 different analog outputs. An 8-bit analog to digital converter (ADC) can measure 256 different analog inputs. Table 1.3.3 illustrates the relationship between precision in binary bits and precision in alternatives. The operation [[x]] is defined as the greatest integer of x. E.g., [[2.1]] [[2.9]] and [[3.0]] are all equal to 3. The Bytes column in Table 2.1 specifies how many bytes of memory it would take to store a number with that precision assuming the data were not packed or compressed in any way.

|

Binary bits |

Bytes |

Alternatives |

|

8 |

1 |

256 |

|

10 |

2 |

1024 |

|

12 |

2 |

4096 |

|

16 |

2 |

65536 |

|

20 |

3 |

1,048,576 |

|

24 |

3 |

16,777,216 |

|

30 |

4 |

1,073,741,824 |

|

32 |

4 |

4,294,967,296 |

|

n |

[[n/8]] |

2n |

Table 1.3.3. Relationship between bits, bytes and alternatives as units of precision.

: How many bytes of memory would it take to store a 50-bit number?

A byte contains 8 bits as shown in Figure 1.3.1, where each bit b7,...,b0 is binary and has the value 1 or 0. We specify b7 as the most significant bit or MSB, and b0 as the least significant bit or LSB.

![]()

Figure 1.3.1. 8-bit binary format.

If a byte is used to represent an unsigned number, then the value of the number is

N = 128•b7 + 64•b6 + 32•b5 + 16•b4 + 8•b3 + 4•b2 + 2•b1 + b0

Notice that the significance of bit n is 2n. There are 256 different unsigned 8-bit numbers. The smallest unsigned 8-bit number is 0 and the largest is 255. For example, 000010102 is 8+2 or 10. The least significant bit can tell us if the number is even or odd.

: Convert the binary number 011010012 to unsigned decimal.

: Convert the hex number 0x54 to unsigned decimal.

The basis of a number system is a subset from which linear combinations of the basis elements can be used to construct the entire set. The basis represents the “places” in a “place-value” system. For positive integers, the basis is the infinite set {1, 10, 100, …}, and the “values” can range from 0 to 9. Each positive integer has a unique set of values such that the dot-product of the value vector times the basis vector yields that number. For example, 2345 is (…, 2,3,4,5)·(…, 1000,100,10,1), which is 2*1000+3*100+4*10+5. For the unsigned 8-bit number system, the basis elements are

{1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128}

The values of a binary number system can only be 0 or 1. Even so, each 8-bit unsigned integer has a unique set of values such that the dot-product of the values times the basis yields that number. For example, 69 is (0,1,0,0,0,1,0,1)·(128,64,32,16,8,4,2,1), which equals 0*128+1*64+0*32+0*16+0*8+1*4+0*2+1*1. Conveniently, there is no other set of 0’s and 1’s, such that set of values multiplied by the basis is 69. In other words, each 8-bit unsigned binary representation of the values 0 to 255 is unique.

One way for us to convert a decimal number into binary is to use the basis elements. The overall approach is to start with the largest basis element and work towards the smallest. More precisely, we start with the most significant bit and work towards the least significant bit. One by one, we ask ourselves whether or not we need that basis element to create our number. If we do, then we set the corresponding bit in our binary result and subtract the basis element from our number. If we do not need it, then we clear the corresponding bit in our binary result. We will work through the algorithm with the example of converting 100 to 8-bit binary, see Table 2.4. We start with the largest basis element (in this case 128) and ask whether or not we need to include it to make 100? Since our number is less than 128, we do not need it, so bit 7 is zero. We go the next largest basis element, 64 and ask, “do we need it?” We do need 64 to generate our 100, so bit 6 is one and we subtract 100 minus 64 to get 36. Next, we go the next basis element, 32 and ask, “do we need it?” Again, we do need 32 to generate our 36, so bit 5 is one and we subtract 36 minus 32 to get 4. Continuing along, we do not need basis elements 16 or 8, but we do need basis element 4. Once we subtract the 4, our working result is zero, so basis elements 2 and 1 are not needed. Putting it together, we get 011001002 (which means 64+32+4).

: In this conversion algorithm, how can we tell if a basis element is needed?

Observation: If the least significant binary bit is zero, then the number is even.

Observation: If the right-most n bits (least sign.) are zero, then the number is divisible by 2n.

Observation: Consider an 8-bit unsigned number system. If bit 7 is low, then the number is between 0 and 127, and if bit 7 is high then the number is between 128 and 255.

: Give the representations of the decimal 45 in 8-bit binary and hexadecimal.

: Give the representations of the decimal 200 in 8-bit binary and hexadecimal.

There are a few techniques for converting decimal numbers to binaries. One of them is consecutive divisions. We start by dividing the decimal number by 2. Then we iteratively divide the result (the quotient) by 2 until the answer is 0. The equivalent binary is formed by the remainders of the divisions. The last remainder found is the most significant digit. Enter a number between 0 and 255 in the following field and click convert to see an example. Try to convert a decimal number to binary.

|

|

|

One of the first schemes to represent signed numbers was called one’s complement. It was called one’s complement because to negate a number, we complement (logical not) each bit. For example, if 25 equals 000110012 in binary, then –25 is 111001102. An 8-bit one’s complement number can vary from ‑127 to +127. The most significant bit is a sign bit, which is 1 if and only if the number is negative. The difficulty with this format is that there are two zeros +0 is 000000002, and –0 is 111111112. Another problem is that one’s complement numbers do not have basis elements. These limitations led to the use of two’s complement.

The two’s complement number system is the most common approach used to define signed numbers. It is called two’s complement because to negate a number, we complement each bit (like one’s complement), then add 1. For example, if 25 equals 000110012 in binary, then –25 is 111001112. If a byte is used to represent a signed two’s complement number, then the value of the number is

N = -128•b7 + 64•b6 + 32•b5 + 16•b4 + 8•b3 + 4•b2 + 2•b1 + b0

Observation: One usually means two’s complement when one refers to signed integers.

There are 256 different signed 8-bit numbers. The smallest signed 8-bit number is -128 and the largest is 127. For example, 100000102 equals -128+2 or -126.

: Convert the signed binary number 110110102 to signed decimal.

: Are the signed and unsigned decimal representations of the 8-bit hex number 0x95 the same or different?

For the signed 8-bit number system the basis elements are

{1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, -128}

Observation: The most significant bit in a two’s complement signed number will specify the sign.

Notice that the same binary pattern of 111111112 could represent either 255 or –1. It is very important for the software developer to keep track of the number format. The computer cannot determine whether the 8‑bit number is signed or unsigned. You, as the programmer, will determine whether the number is signed or unsigned by the specific assembly instructions you select to operate on the number. Some operations like addition, subtraction, and shift left (multiply by 2) use the same hardware (instructions) for both unsigned and signed operations. On the other hand, divide, and shift right (divide by 2) require separate hardware (instruction) for unsigned and signed operations.

Observation: To take the negative of a two’s complement signed number we first complement (flip) all the bits, then add 1.

A second way to convert negative numbers into binary is to first convert them into unsigned binary, then do a two’s complement negate. For example, we earlier found that +100 is 011001002. The two’s complement negate is a two-step process. First we do a logic complement (flip all bits) to get 100110112. Then add one to the result to get 100111002.

: Give the representations of -54 in 8-bit binary and hexadecimal.

: Why can’t you represent the number 150 using 8-bit signed binary?

When dealing with numbers on the computer, it will be convenient to memorize some Powers of 2 as shown in Table 1.3.4.

|

exponent |

decimal |

|

20 |

1 |

|

21 |

2 |

|

22 |

4 |

|

23 |

8 |

|

24 |

16 |

|

25 |

32 |

|

26 |

64 |

|

27 |

128 |

|

28 |

256 |

|

29 |

512 |

|

210 |

1024 about a thousand |

|

211 |

2048 |

|

212 |

4096 |

|

213 |

8192 |

|

214 |

16384 |

|

215 |

32768 |

|

216 |

65536 |

|

220 |

about a million |

|

230 |

about a billion |

|

240 |

about a trillion |

Table 1.3.4. Some powers of two that will be useful to memorize.

: Use Table 1.3.4 to determine the approximate value of 232?

A halfword or double byte contains 16 bits, where each bit b15,...,b0 is binary and has the value 1 or 0, as shown in Figure 1.3.2.

![]()

Figure 1.3.2. 16-bit binary format.

If a halfword is used to represent an unsigned number, then the value of the number is

N = 32768•b15 + 16384•b14 + 8192•b13 + 4096•b12

+ 2048•b11 + 1024•b10 + 512•b9 + 256•b8

+ 128•b7 + 64•b6 + 32•b5 + 16•b4 + 8•b3 + 4•b2 + 2•b1 + b0

There are 65536 different unsigned 16-bit numbers. The smallest unsigned 16-bit number is 0 and the largest is 65535. For example, 00100001100001002 or 0x2184 is 8192+256+128+4 or 8580.

: Convert the 16-bit binary number 00100000011010102 to unsigned decimal.

: Convert the 16-bit hex number 0x1234 to unsigned decimal.

For the unsigned 16-bit number system the basis elements are

{1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, 512, 1024, 2048, 4096, 8192, 16384, 32768}

: Convert the unsigned decimal number 1234 to 16-bit hexadecimal.

: Convert the unsigned decimal number 10000 to 16-bit binary.

There are also 65536 different signed 16-bit numbers. The smallest two’s complement signed 16‑bit number is –32768 and the largest is 32767. For example, 11010000000001002 or 0xD004 is –32768+16384+4096+4 or –12284.

If a halfword is used to represent a signed two’s complement number, then the value of the number is

N = -32768•b15 + 16384•b14 + 8192•b13 + 4096•b12

+ 2048•b11 + 1024•b10 + 512•b9 + 256•b8

+ 128•b7 + 64•b6 + 32•b5 + 16•b4 + 8•b3 + 4•b2 + 2•b1 + b0

: Convert the 16-bit hex number 0x1234 to signed decimal.

: Convert the 16-bit hex number 0xABCD to signed decimal.

For the signed 16-bit number system the basis elements are

{1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, 512, 1024, 2048, 4096, 8192, 16384, -32768}

Common Error: An error will occur if you use 16-bit operations on 8-bit numbers, or use 8-bit operations on 16-bit numbers.

Maintenance Tip: To improve the clarity of your software, always specify the precision of your data when defining or accessing the data.

: Convert the signed decimal number 1234 to 16-bit hexadecimal.

: Convert the signed decimal number –10000 to 16-bit binary.

A word on the ARM Cortex M will have 32 bits. Consider an unsigned number with 32 bits, where each bit b31,...,b0 is binary and has the value 1 or 0. If a 32-bit number is used to represent an unsigned integer, then the value of the number is

N = 231 • b31 + 230 • b30 + ... + 2•b1 + b0 = sum(2i • bi) for i=0 to 31

There are 232 different unsigned 32-bit numbers. The smallest unsigned 32-bit number is 0 and the largest is 232-1. This range is 0 to about 4 billion. For the unsigned 32-bit number system, the basis elements are

{1, 2, 4, ... , 229, 230, 231}

If a 32-bit binary number is used to represent a signed two’s complement number, then the value of the number is

N = -231 • b31 + 230 • b30 + ... + 2•b1 + b0 = -231 • b31 + sum(2i • bi) for i=0 to 30

There are also 232 different signed 32-bit numbers. The smallest signed 32-bit number is -231 and the largest is 231-1. This range is about -2 billion to about +2 billion. For the signed 32-bit number system, the basis elements are

{1, 2, 4, ... , 229, 230, -231}

The computer does not distinguish between signed and unsigned numbers in memory. The interpretation is yours to make. Enter an 8-bit binary number in the following field and press "show" to see its value if interpreted as signed or unsigned integer. For convenience, you can also enter hexadecimal input with '0x' prefix.

Video 1.3.3. Signed versus unsigned numbers

1.4. Introduction to Computers

Video 1.4.1. Computer Organization

A computer combines a processor, random access memory (RAM), read only memory (ROM), and input/output (I/O) ports. Computers are not intelligent. Rather, you are the true genius. Computers are electronic idiots. They can store a lot of data, but they will only do exactly what we tell them to do. Fortunately, however, they can execute our programs quite quickly, and they don’t get bored doing the same tasks over and over again. Software is an ordered sequence of very specific instructions that are stored in memory, defining exactly what and when certain tasks are to be performed. It is a set of instructions, stored in memory, that are executed in a complicated but well-defined manner. The processor executes the software by retrieving and interpreting these instructions one at a time. A microprocessor is a small processor, where small refers to size (i.e., it fits in your hand) and not computational ability.

A microcomputer is a small computer, where again small refers to size (i.e., you can carry it) and not computational ability. For example, a desktop PC is a microcomputer. Small in this context describes its size not its computing power. Consequently, there can be great confusion over the term microcomputer, because it can refer to a very wide range of devices from a PIC12C508, which is an 8-pin chip with 512 words of ROM and 25 bytes RAM, to the most powerful I7-based personal computer.

A port is a physical connection between the computer and its outside world. Ports allow information to enter and exit the system. Information enters via the input ports and exits via the output ports. Other names used to describe ports are I/O ports, I/O devices, interfaces, or sometimes just devices. A bus is a collection of wires used to pass information between modules.

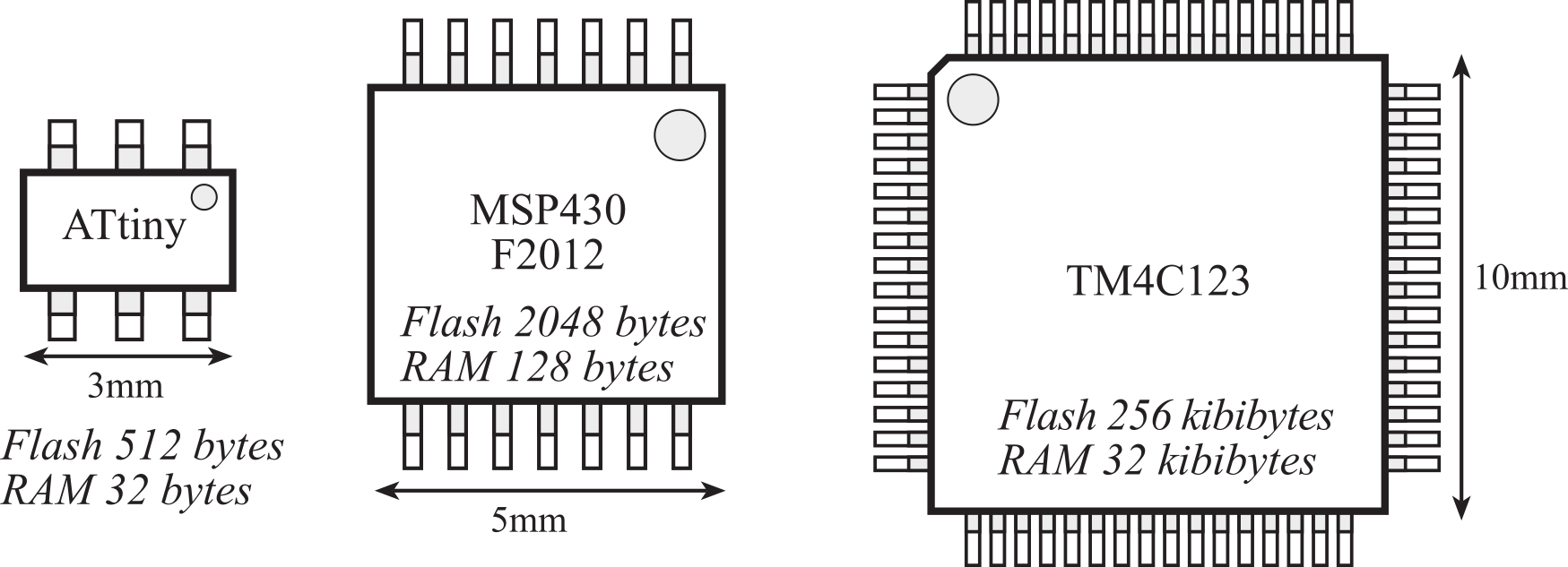

A very small microcomputer, called a microcontroller, contains all the components of a computer (processor, memory, I/O) on a single chip. As shown in Figure 1.4.1, the Atmel ATtiny, the Texas Instruments MSP430, and the Texas Instruments TM4C123 are examples of microcontrollers. Because a microcomputer is a small computer, this term can be confusing because it is used to describe a wide range of systems from a 6-pin ATtiny4 running at 1 MHz with 512 bytes of program memory to a personal computer with state-of-the-art 64-bit multi-core processor running at multi-GHz speeds having terabytes of storage.

The computer can store information in RAM by writing to it, or it can retrieve previously stored data by reading from it. RAMs are volatile; meaning if power is interrupted and restored the information in the RAM is lost.

Figure 1.4.1. A microcontroller is a complete computer on a single chip.

Information is programmed into ROM using techniques more complicated than writing to RAM. From a programming viewpoint, retrieving data from a ROM is identical to retrieving data from RAM. ROMs are nonvolatile; meaning if power is interrupted and restored the information in the ROM is retained.

Figure 1.4.2 shows a simplified block diagram of a microcontroller based on the ARM® Cortex™-M processor. It is a Harvard architecture because it has separate data and instruction buses. Instructions are fetched from flash ROM using the ICode bus at the same time as Data are exchanged with memory and I/O via the System bus interface.

Figure 1.4.2. Harvard architecture of an ARM® Cortex-M-based microcontroller.

: What are the differences between a microcomputer, a microprocessor, and a microcontroller?

: What are three differences between RAM and ROM?

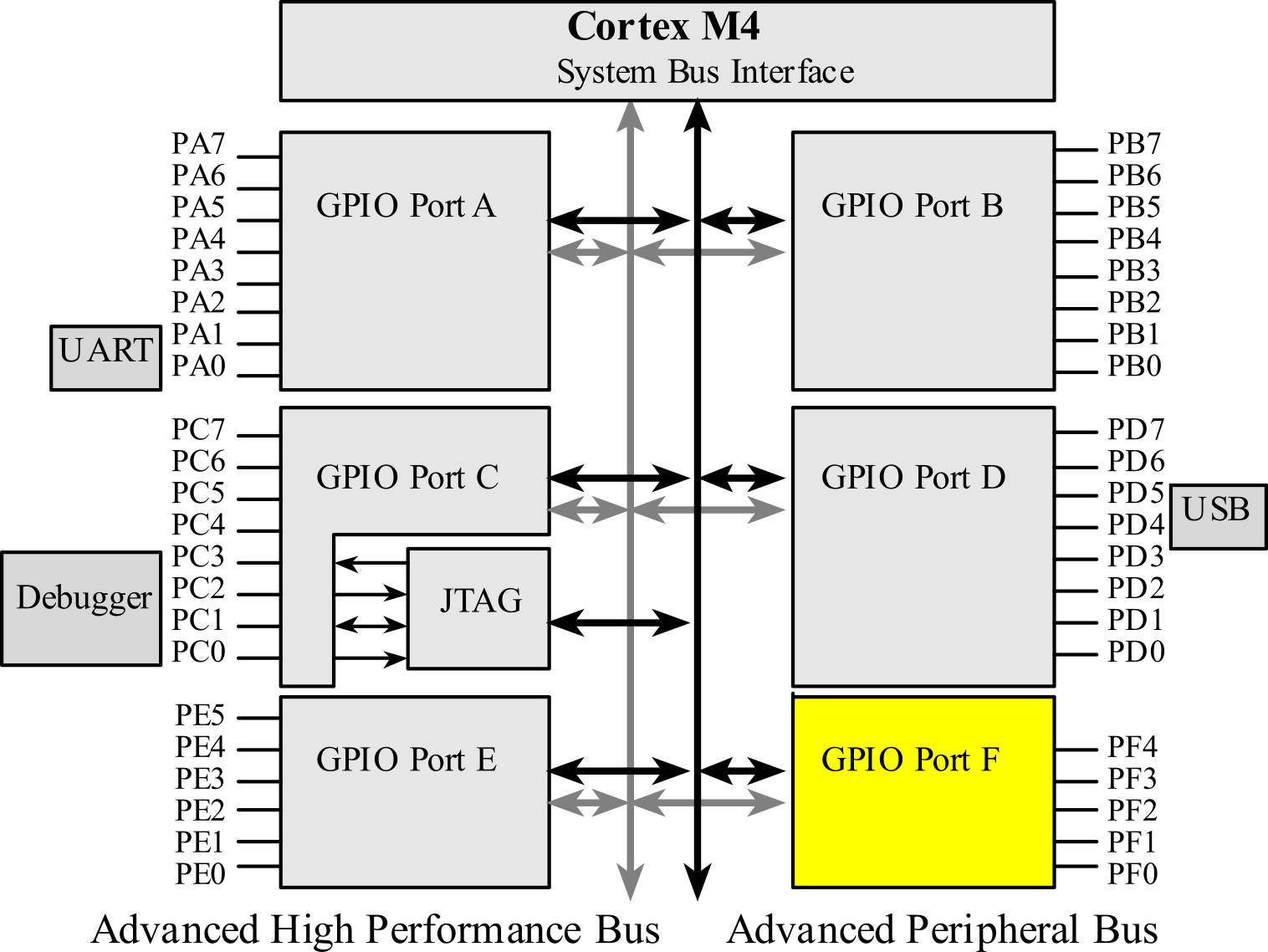

1.5. I/O Ports

The external devices attached to the microcontroller provide functionality for the system. A pin is one wire on the microcontroller used for input or output. There are 43 I/O pins on the TM4C123. A port is a collection of pins. An input pin is hardware on the microcontroller that allows information about the external world to be entered into the computer. The microcontroller also has hardware called an output pin to send information out to the external world. Most of the pins shown in Figure 5.1.1 are input/output ports.

Video 1.5.1. I/O Ports and Interfacing

An interface is defined as the collection of the I/O port, external electronics, physical devices, and the software, which combine to allow the computer to communicate with the external world. An example of an input interface is a switch, where the operator toggles the switch, and the software can recognize the switch position. An example of an output interface is a light-emitting diode (LED), where the software can turn the light on and off, and the operator can see whether or not the light is shining. There is a wide range of possible inputs and outputs, which can exist in either digital or analog form. In general, we can classify I/O interfaces into four categories

Parallel - binary data are available simultaneously on a group of lines

Serial - binary data are available one bit at a time on a single line

Analog - data are encoded as an electrical voltage, current, or power

Time - data are encoded as a period, frequency, pulse width, or phase shift

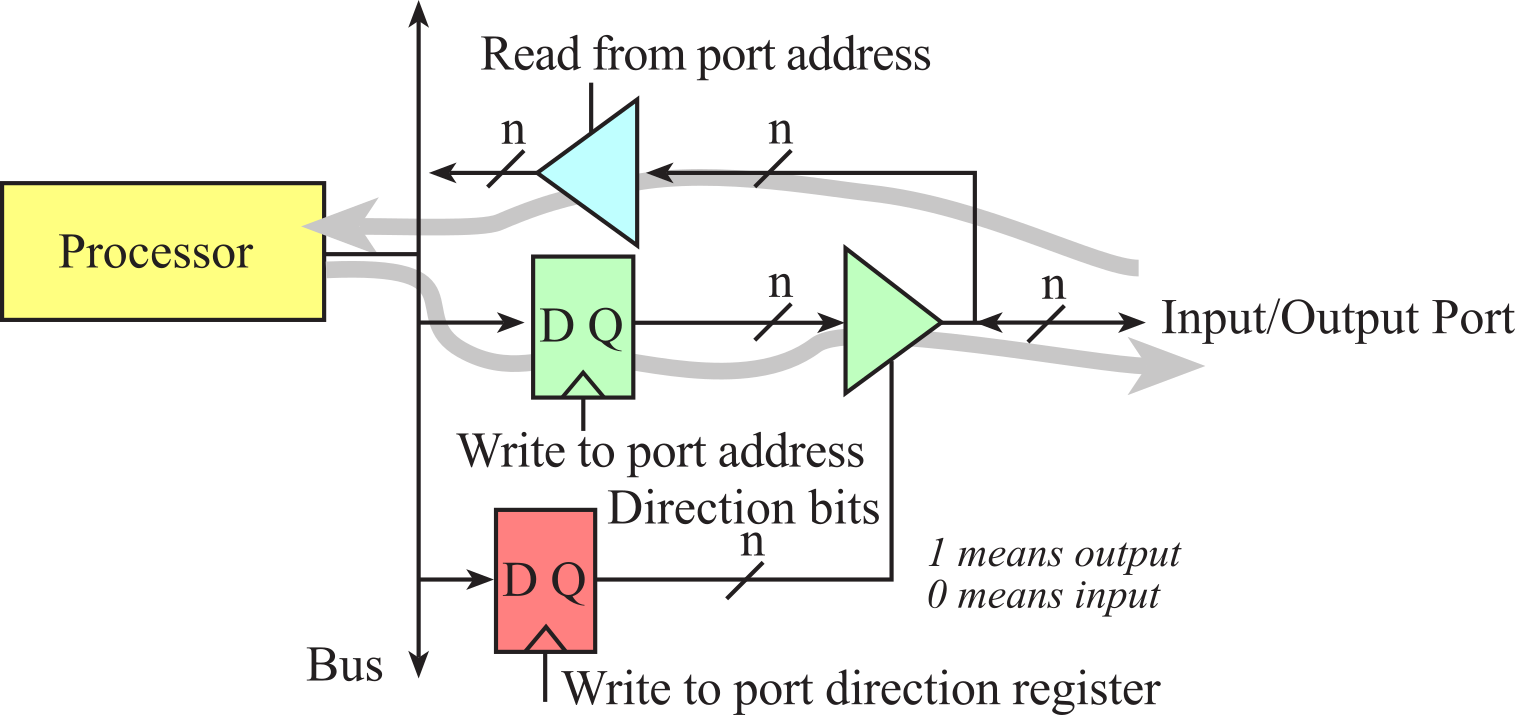

The general purpose input output (GPIO) port is simply a collection of pins, and allows the software to read data from input pins and write data to output pins. The direction register allows the software to specify whether a pin is an input or output.

Figure 1.5.2. A GPIO port allows for input and output.

Figure 1.5.3. The TM4C123GH6PM six ports and 43 pins.

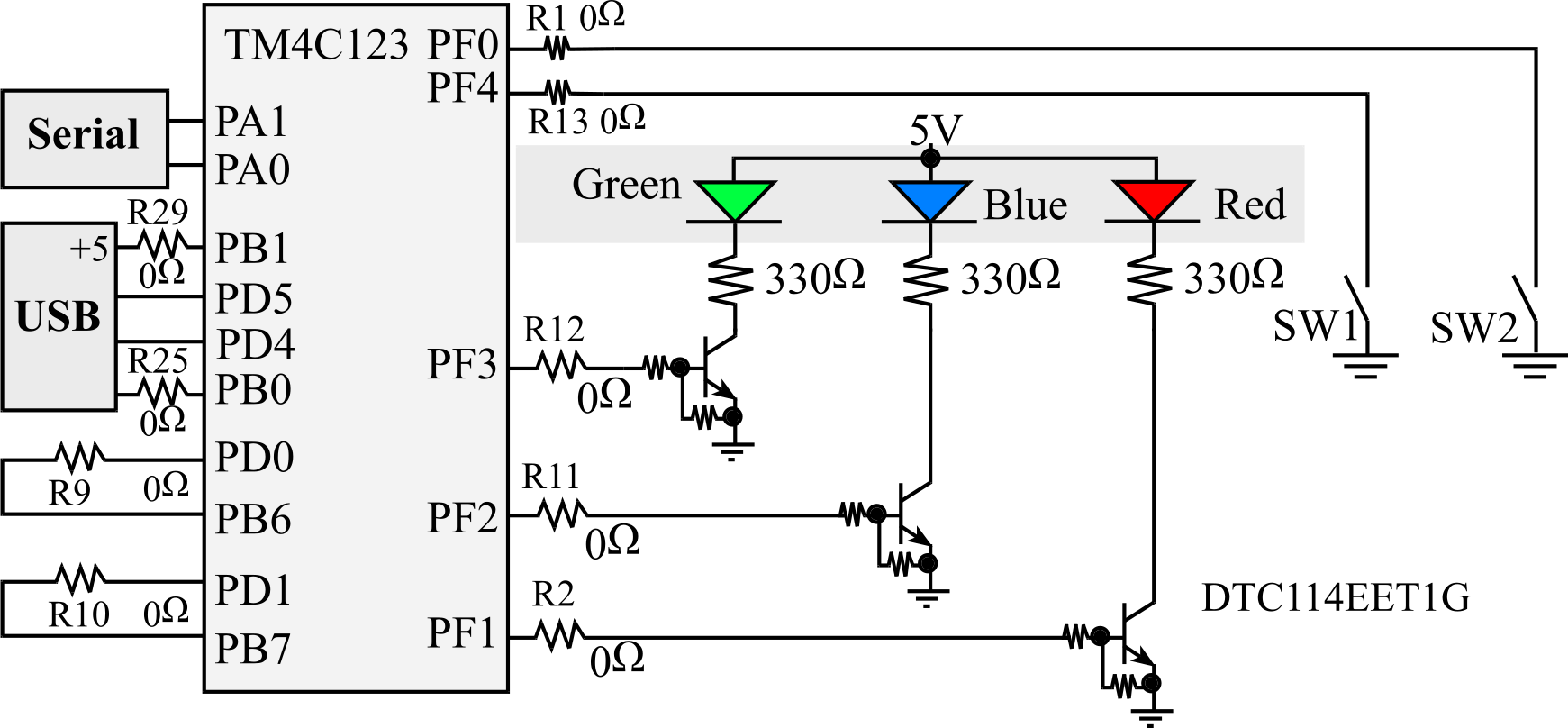

We will begin by interacting with Port F, because the LaunchPad has two switches and one LED already connected. The 5 pins of Port F are called PF4, PF3, PF3, PF2, PF1, and PF0. Figure 1.5.4 shows there are switches connected to PF4 and PF0. There is one 3-color LED connected to PF3-PF2-PF1.

Figure 1.5.4. Switch and LED interfaces on the LaunchPad Evaluation Board. The zero ohm resistors can be removed so the corresponding pin can be used without connection to the external circuits.

An I/O register is a location in memory with which software can interface with the I/O port. Initialization is executed once at the beginning. First, we turn on the clock in SYSCTL_RCGCGPIO_R by setting appropriate bits. Second, we wait about 25, which is two bus cycles. Third, we write 1 into the corresponding DIR bit for each pin we wish to make output. Conversely we write a 0 into the corresponding DIR bit for each pin we wish to make input. To use the two switches on PF4 and PF0, we will also set bits 4 and 0 of the PUR register to activate an internal pull-up resistor. Lastly, we set the DEN bits to 1 to enable data pins. If we wish to input from a Port F GPIO pin we simply read from GPIO_PORTF_DATA_R. Reading from GPIO_PORTF_DATA_R obtains the current values for both input and output pins. If we wish to output to a Port F GPIO pin we write to GPIO_PORTF_DATA_R. Writing to GPIO_PORTF_DATA_R affects output pins but does not affect input pins. Table 1.5.1 shows the addresses of some of the I/O registers needed to access Port F. The other ports have similar I/O registers.

| Address | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | Name |

| 0x400FE608 | - | - | GPIOF | GPIOE | GPIOD | GPIOC | GPIOB | GPIOA | SYSCTL_RCGCGPIO_R |

| 0x400253FC | - | - | - | DATA | DATA | DATA | DATA | DATA | GPIO_PORTF_DATA_R |

| 0x40025400 | - | - | - | DIR | DIR | DIR | DIR | DIR | GPIO_PORTF_DIR_R |

| 0x40025510 | - | - | - | PUR | PUR | PUR | PUR | PUR | GPIO_PORTF_PUR_R |

| 0x4002551C | - | - | - | DEN | DEN | DEN | DEN | DEN | GPIO_PORTF_DEN_R |

Table 1.5.1. I/O registers needed for GPIO Port F.

: How does the software input from Port F?

: How does the software output to Port F?

1.6. Memory

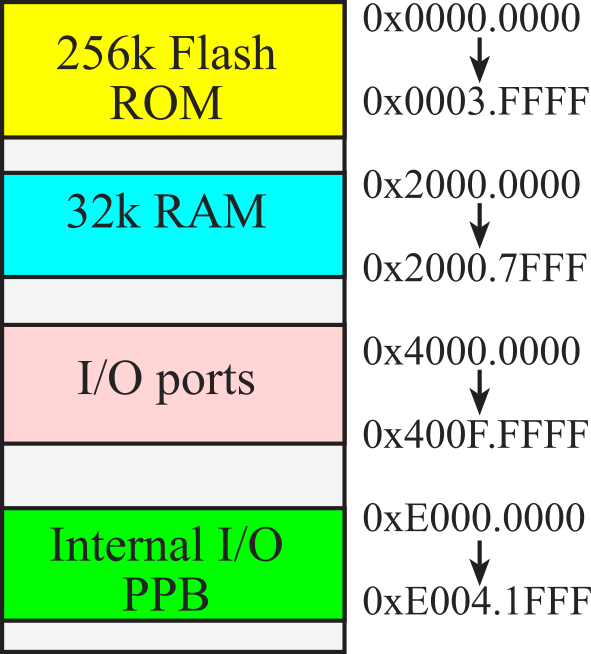

Figure 1.6.1 shows the memory map of the TM4C123. A 32-bit entry requires four sequential locations. The I/O ports exist as memory-mapped locations. I/O ports are not memory, but we will write to an I/O port address to output and read from an I/O port address to input.

Figure 1.6.1. Memory map. Each address contains 8 bits or 1 byte.

Video 1.6.1. Memory Map Layout

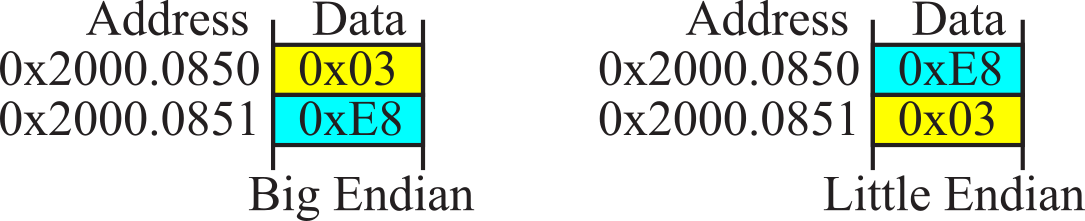

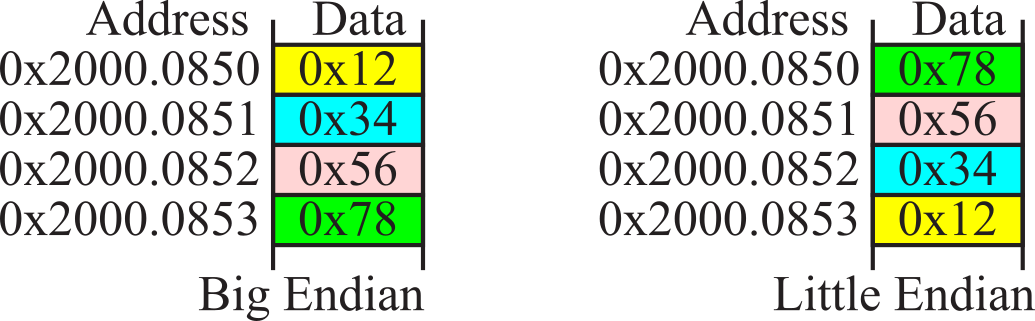

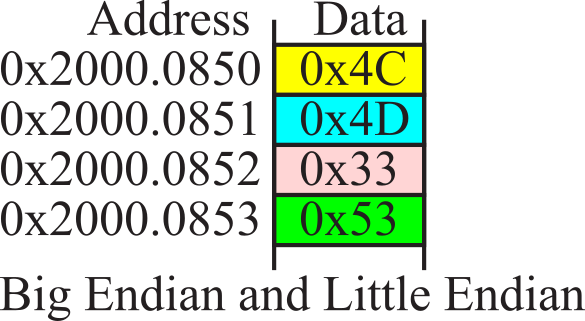

When we store 16-bit data into memory it requires two bytes. Since the memory systems on most computers are byte addressable (a unique address for each byte), there are two possible ways to store in memory the two bytes that constitute the 16-bit data. Many main-frame computers, like the z/Architecture, implement the big endian approach that stores the most significant byte at the lower address. Most smaller computers (desktops, laptops, phones and microcontrollers) implement the little endian approach that stores the least significant byte at the lower address. The Cortex-M microcontrollers use the little endian format. Many ARM processors are biendian, because they can be configured to efficiently handle both big and little endian data. Instruction fetches on the ARM are always little endian. Figure 1.6.2 shows two ways to store the 16-bit number 1000 (0x03E8) at locations 0x20000850 and 0x20000851. We also could use either the big or little endian approach when storing 32-bit numbers into memory that is byte (8-bit) addressable. Figure 1.6.3 shows the big and little endian formats that could be used to store the 32-bit number 0x12345678 at locations 0x20000850 through 0x20000853.

Figure 1.6.2. Example of big and little endian formats of a 16-bit number (the Cortex M used little endian).

Figure 1.6.3. Example of big and little endian formats of a 32-bit number (the Cortex M used little endian).

In the previous two examples, we normally would not pick out individual bytes (e.g., the 0x12), but rather capture the entire multiple byte data as one nondivisable piece of information. On the other hand, if each byte in a multiple byte data structure is individually addressable, then both the big and little endian schemes store the data in first to last sequence. For example, if we wish to store the four ASCII characters ‘LM3S’, which is 0x4C4D3353 at locations 0x2000.0850 through 0x2000.0853, then the ASCII ‘L’=0x4C comes first in both big and little endian schemes, as illustrated in Figure 1.6.4.

Figure 1.6.4. Character strings are stored in the same for both big and little endian formats.

The terms “big and little endian” come from Jonathan Swift’s satire Gulliver’s Travels. In Swift’s book, a Big Endian refers to a person who cracks their egg on the big end. The Lilliputians were Little Endians because they insisted that the only proper way is to break an egg on the little end. The Lilliputians considered the Big Endians as inferiors. The Big and Little Endians fought a long and senseless war over the best way to crack an egg.

Common Error: An error will occur when data is stored in Big Endian by one computer and read in Little Endian format on another.

A pseudo-op is an assembler directive to affect the assembly process. We use the AREA pseudo-op to specify what information goes in RAM and what goes in ROM. We will use a template similar to Program 1.6.1 for most assembly programs in this class. The EQU pseudo-ops create symbols containing the address of some the I/O port registers. The AREA DATA pseudo-op means the following code will be placed in volatile RAM. The SPACE pseudo-op allocates 4 bytes (in RAM) for the variable named Stuff. The AREA |.text| pseudo-op means the following code will be placed in nonvolatile ROM. The THUMB pseudo-op tells the assembler to create Thumb code. The EXPORT pseudo-op allows the label Start to be accessed from another file. In particular, Start will be the place the software starts on power up or on reset. The B Loop instruction creates an infinite loop, typical of embedded systems, causing the code between Loop and B Loop to be executed over and over.

GPIO_PORTF_DATA_R EQU 0x400253FC

GPIO_PORTF_DIR_R EQU 0x40025400

GPIO_PORTF_PUR_R EQU 0x40025510

GPIO_PORTF_DEN_R EQU 0x4002551C

SYSCTL_RCGCGPIO_R EQU 0x400FE608

AREA DATA, ALIGN=4

;Global variables defined here, will go in RAM

Stuff SPACE 4

AREA |.text|, CODE, READONLY, ALIGN=2

THUMB

EXPORT Start

Start

;assembly code to be executed once and first goes here

Loop

;assembly code to be executed over and over goes here

B Loop

END ; end of

file

Program 1.6.1. Template for assembly language programs.

: What is the purpose of the 4 in the Stuff SPACE 4 pseudo-op?

: What is the purpose of the AREA Data pseudo-op?

: What is the purpose of the AREA |.text| pseudo-op?

1.7. Instruction Set Architecture

Video 1.7.1. Instruction set architecture.

This section is a brief introduction to the ARM® Cortex™-M instruction set architecture. There are many ARM® processors, and this class focuses on Cortex-M microcontrollers, which executes Thumb® instructions extended with Thumb-2 technology. This class will not describe in detail all the Thumb instructions. Rather, we focus on only a subset of the Thumb® instructions. This subset will be functionally complete without regard to minimizing code size or optimizing for execution speed. Furthermore, we will show the simple forms of instructions, but in many cases there are specific restrictions on which registers can be used and the sizes of the constants. Bookmark the following links and refer to them as you write assembly programs

- Quick Reference Assembly Guide (ARM)

- Assembly Reference (Yerraballi/Valvano)

- Cortex-M3/M4F Instruction Set (Texas Instruments)

- The ARM Cortex-M Technical Reference Manual (ARM)

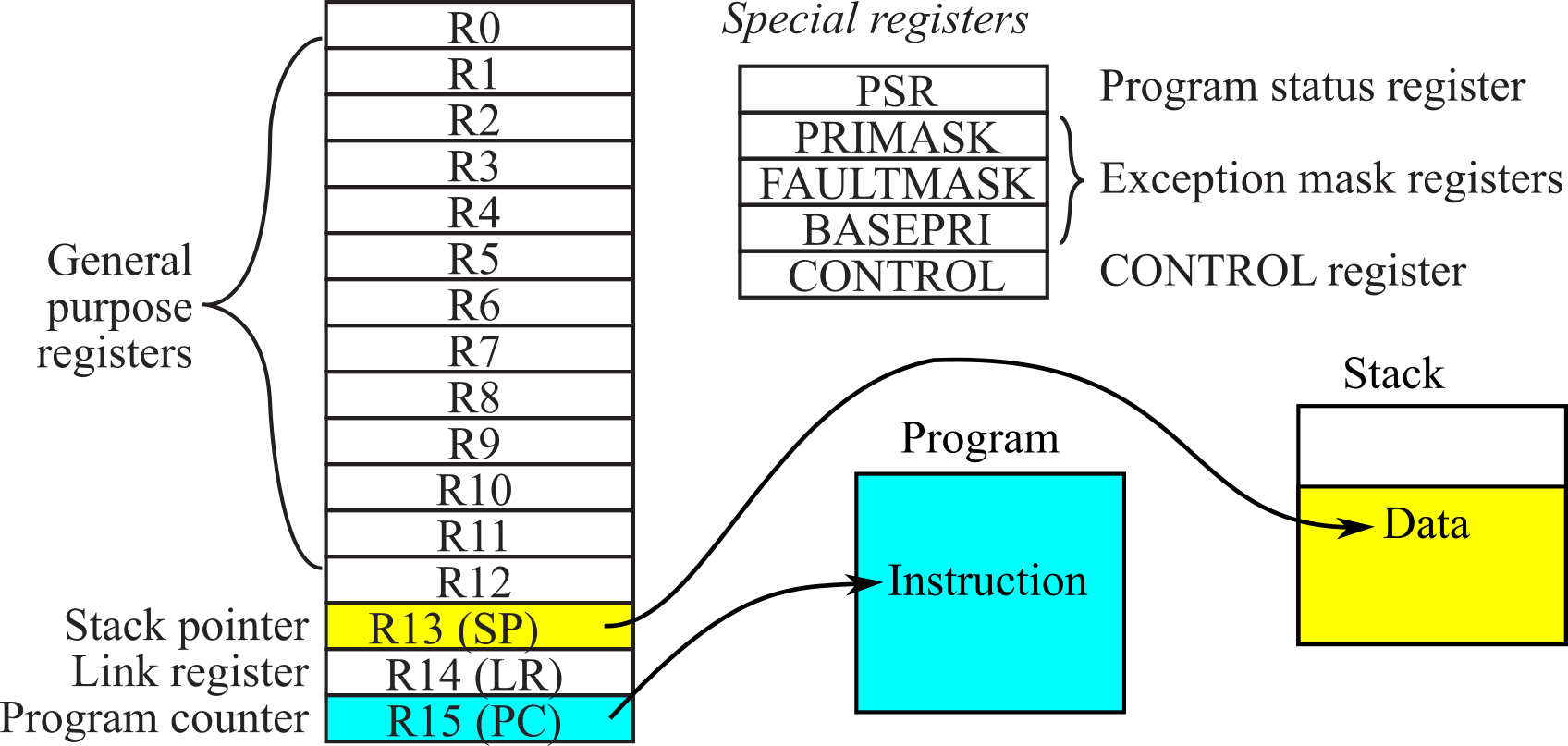

1.7.1. Registers

Registers are high-speed storage inside the processor. The registers are depicted in Figure 1.6.1. R0 to R12 are general purpose registers and contain either data or addresses. Register R13 (also called the stack pointer, SP) points to the top element of the stack. Register R14 (also called the link register, LR) is used to store the return location for functions. The LR is also used in a special way during exceptions, such as interrupts. Interrupts are covered in Chapter 6. Register R15 (also called the program counter, PC) points to the next instruction to be fetched from memory. The processor fetches an instruction using the PC and then increments the PC.

Figure 1.6.1. Registers on the ARM® Cortex-M processor.

: Where in memory should you put the stack? I.e., does the SP point to RAM or ROM?

: Where in memory should you put the program? I.e., does the PC point to RAM or ROM?

The ARM Architecture Procedure Call Standard, AAPCS, part of the ARM Application Binary Interface (ABI), uses registers R0, R1, R2, and R3 to pass input parameters into a C function. Also according to AAPCS we place the return parameter in Register R0.

There are three status registers named Application Program Status Register (APSR), the Interrupt Program Status Register (IPSR), and the Execution Program Status Register (EPSR) as shown in Figure 1.7.2. These registers can be accessed individually or in combination as the Program Status Register (PSR). The N, Z, V, C, and Q bits give information about the result of a previous ALU operation. In general, the N bit is set after an arithmetical or logical operation signifying whether or not the result is negative. Similarly, the Z bit is set if the result is zero. The C bit means carry and is set on an unsigned overflow, and the V bit signifies signed overflow. The Q bit indicates that “saturation” has occurred – while you might want to look it up, saturated arithmetic is beyond the scope of this class.

Figure 1.7.2. The program status register of the ARM® Cortex-M processor.

The T bit will always be 1, indicating the ARM® Cortex™-M processor is executing Thumb® instructions. The ISR_NUMBER indicates which interrupt if any the processor is handling. Bit 0 of the special register PRIMASK is the interrupt mask bit. If this bit is 1, most interrupts and exceptions are not allowed. If the bit is 0, then interrupts are allowed. The nonmaskable interrupt (NMI) is not affected by these mask bits. The BASEPRI register defines the priority of the executing software. It prevents interrupts with lower or equal priority but allows higher priority interrupts. For example if BASEPRI equals 3, then requests with level 0, 1, and 2 can interrupt, while requests at levels 3 and higher will be postponed. A lower number means a higher priority interrupt. The details of interrupt processing will be presented in Chapter 6.

1.7.2. Syntax

Assembly language instructions have four fields separated by spaces or tabs. The label field is optional and starts in the first column and is used to identify the position in memory of the current instruction. You must choose a unique name for each label. The opcode field specifies the processor command to execute. The operand field specifies where to find the data to execute the instruction. Thumb instructions have 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 operands, separated by commas. The comment field is also optional and is ignored by the assembler, but it allows you to describe the software making it easier to understand. You can add optional spaces between operands in the operand field. However, a semicolon must separate the operand and comment fields. Good programmers add comments to explain the software.

Label Opcode Operands Comment

Func

MOV

R0,

#100

; 100 means maximum

BX

LR

Observation: A good comment explains why an operation is being performed, how it is used, how it can be changed, or how it was debugged. A bad comment explains what the operation does. The comments in the above two assembly lines are examples of bad comments.

The assembly source code is a text file (with Windows file extension .s) containing a list of instructions. The assembler translates assembly source code into object code, which are the machine instructions executed by the processor. All object code is halfword-aligned. This means instructions can be 16 or 32 bits wide, and the program counter bit 0 will always be 0. The listing is a text file containing a mixture of the object code generated by the assembler together with our original source code.

Address Object code Label Opcode Operand comment

0x000005E2 F04F0164 Func MOV R1,#0x64 ; R1=100

0x000005E6 FB00F001 MUL R0,R0,R1 ; R0=100*input

0x000005EA F100000A ADD R0,R0,#0x0A ; R0=100*input+10

0x000005EE 4770 BX LR ; return 100*input+10

When we build a project all files are assembled or compiled then linked together. The address values shown in the listing are relative to the particular file being assembled. When the entire project is built, the files are linked together, and the linker decides exactly where in memory everything will be. After building the project, it can be downloaded, which programs the object code into flash ROM. You are allowed to load and execute software out of RAM. But for an embedded system, we typically place executable instructions into nonvolatile ROM. The listing you see in the debugger will specify the absolute address showing you exactly where in memory your variables and instructions exist.

1.7.3. Reading from and writing to memory

The first action we present is bringing a constant value into a register. With immediate addressing mode, the data itself is contained in the instruction. Once the instruction is fetched no additional memory access cycles are required to get the data. Notice the number 100 (0x64) is embedded in the machine code of the MOV instruction shown in Figure 1.6.3.

MOV R0,#100 ; R0=100, immediate addressing

Figure 1.7.3. An example of immediate addressing mode, data is in the instruction.

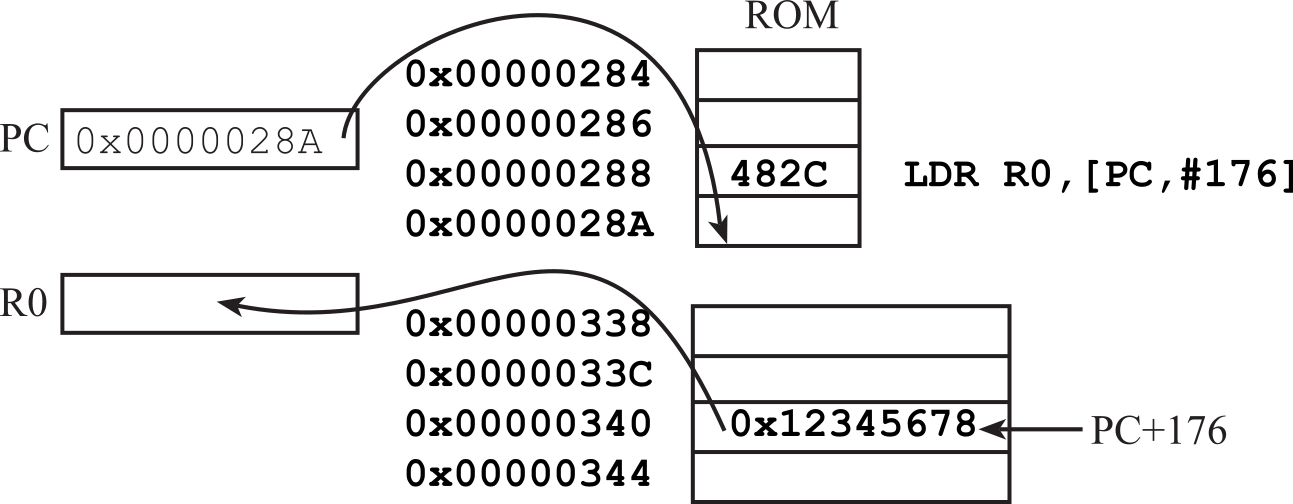

The constant value allowed by MOV is limited to 16-bit values. On the other hand, the LDR instruction can be used to bring any 32-bit value into a register. Notice the number 0x12345678 is not embedded in the machine code of the instruction, but rather stored in ROM a short distance away, as shown in Figure 1.7.4. The Keil assembler automatically places the constant in ROM and calculates the appropriate PC-relative offset. At the time of execution, the PC is pointing to the next instruction.

LDR R0,=0x12345678 ; R0=0x12345678, PC-relative addressing

Figure 1.7.4. An example of using the LDR instruction to load any constant into a register.

Video 1.7.2. Assembly language access to RAM and ROM variables.

A fundamental issue in program development is the

differentiation between data and address. When we put the number 100

into Register R0, whether this is data or address depends on how the 100

is used. As presented in Program 1.6.1, we created a 32-bit global

variable called Stuff. To write an initial value of 100 into

this variable will take three instructions. In this example, R0 has data

and R1 had an address. First, the MOV instruction brings the

desired value into R0. Second, the LDR instruction sets R1 to

point to the global variable Stuff. Lastly, the STR instruction

writes the value into the variable.

MOV R0,#100

LDR

R1,=Stuff ; R1 points to the variable Stuff

STR

R0,[R1] ; Stuff=100

Figure 1.7.5. It takes three instructions to write to a global variable.

: How would you modify the above assembly code to write 0x0E to Port F?

To read the value of a variable into a register

will take two instructions. After executing these two instructions, R3

will have a copy of the value from the global Stuff. The first LDR

instruction sets R2 to point to the global variable Stuff.

The second LDR instruction will read the value from the

variable.

LDR R2,=Stuff ; R2 points to the variable

Stuff

LDR

R3,[R2] ; R3=Stuff

Figure 1.7.6. It takes two instructions to read from a global variable.

: How would you modify the above assembly code to read from Port F?

An aligned access is an operation where a word-aligned address is used for a word, dual word, or multiple word access, or where a halfword-aligned address is used for a halfword access. Byte accesses are always aligned. The address of an aligned word access will have its bottom two bits equal to zero. An unaligned word access means we are accessing a 32-bit object (4 bytes) but the address is not evenly divisible by 4. The following instructions support 32-bit memory access:

LDR Load 32-bit word

STR Store 32-bit word

The address of an aligned halfword access will have its bottom bit equal to zero. An unaligned halfword access means we are accessing a 16-bit object (2 bytes) but the address is not evenly divisible by 2. The following instructions support 16-bit memory access:

LDRH Load 16-bit unsigned halfword

LDRSH Load 16-bit signed halfword (sign extend bit 15 to bits 31-16)

STRH Store 16-bit halfword

Transfers of one byte are allowed for the following instructions:

LDRB Load 8-bit unsigned byte

LDRSB Load 8-bit signed byte (sign extend bit 7 to bits 31-8)

STRB Store 8-bit byte

When loading a 32-bit register with an 8- or 16-bit value, it is important to use the proper load, depending on whether the number being loaded is signed or unsigned. This determines what is loaded into the most significant bits of the register to ensure that the number keeps the same value when it is promoted to 32 bits. When loading an 8-bit unsigned number, the top 24 bits of the register will become zero. When loading an 8-bit signed number, the top 24 bits of the register will match bit 7 of the memory data (signed extend). Note that there is no such thing as a signed or unsigned store. For example, there is no STRSH; there is only STRH. This is because 8, 16, or all 32 bits of the register are stored to an 8-, 16-, or 32-bit location, respectively. No promotion occurs. This means that the value stored to memory can be different from the value located in the register if there is overflow. When using STRB to store an 8-bit number, be sure that the number in the register is 8 bits or less.

Figure 1.7.6. Assume these memory contents for Checkpoints 1.7.5 through 1.7.9.

: Assume R0 equal 0x20000850 at the time LDR R1,[R0] is executed. To what value will R1 become?

: Assume R0 equal 0x20000850 at the time LDRH R2,[R0] is executed. To what value will R2 become?

: Assume R0 equal 0x20000850 at the time LDRSH R3,[R0] is executed. To what value will R3 become?

: Assume R0 equal 0x20000850 at the time LDRB R4,[R0] is executed. To what value will R4 become?

: Assume R0 equal 0x20000850 at the time LDRSB R5,[R0] is executed. To what value will R5 become?

1.7.4. Logical Operations

Boolean Logic has two states: true (1) and false (0). A binary operation produces a single result given two inputs. The logical and (&) operation yields a true result if both input parameters are true. The logical or (|) operation yields a true result if either input parameter is true. The exclusive or (^) operation yields a true result if exactly one input parameter is true. The logical operators are summarized in the table below. The logical instructions on the ARM Cortex-M processor take two inputs, one from a register and the other either from a register or from a constant. These operations are performed in a bit-wise fashion on two 32-bit input parameters yielding one 32-bit output result. The result is stored into the destination register. For example, the calculation r=m&n means each bit is calculated separately, r31=m31&n31, r30=m30&n30,..., r0=m0&n0.

In C, when we write logical operations as

r=m&n; r=m|n; r=m^n; the logical operation occurs in a bit-wise

fashion also described by the table below. However, in C, we define the

Boolean functions as r=m&&n; r=m||n; For Booleans, the operation

occurs in a word-wise fashion. For example, r=m&&n; means r will

become zero if either m is zero or n is zero. Conversely, r will become

1 (any nonzero) if both m is nonzero and n is nonzero.

| A | B | A&B | A|B | A^B | A&(~B) |

| Rn | Op2 | AND | ORR | EOR | BIC |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

Table 1.7.1. Logical operations performed by the Cortex-M processor.

All instructions place the result into the

destination register Rd. If Rd is omitted, the result

is placed into Rn, which is the register holding the first

operand. If the optional S suffix is added, the N and Z condition code

bits are updated on the result of the operation. The second operand is

either a register or a 12-bit immediate value. We use the AND instruction

to mask or select bits. We use the ORR instruction to set bits.

We use the EOR instruction to toggle bits (change from 0 to 1

or 1 to 0) bits. We use the BIC instruction to clear bits.

AND Rd, Rn, Rm ;Rd=Rn&Rm

AND Rd, Rn, #n ;Rd=Rn&n

ORR Rd, Rn, Rm ;Rd=Rn|Rm

ORR Rd, Rn, #n ;Rd=Rn|n

EOR Rd, Rn, Rm ;Rd=Rn^Rm

EOR Rd, Rn, #n ;Rd=Rn^n

BIC Rd, Rn, Rm ;Rd=Rn&(~Rm)

BIC Rd, Rn, #n ;Rd=Rn&(~n)

Assume Port F bit 1 (PF1) is an output. The

following example sets the PF1 pin high. Notice that this code will

leave the other pins unchanged.

// C version

GPIO_PORTF_DATA_R

= GPIO_PORTF_DATA_R | 0x02;

; assembly version

LDR R0,=GPIO_PORTF_DATA_R ;pointer to data register

LDR

R1,[R0]

;previous values

ORR

R1,R1,#0x02

;set bit 1

STR

R0,[R1] ; change output

Again, assume Port F bit 1 (PF1) is an output. The

following example clears the PF1 pin low, without changing any other

pins.

// C version

GPIO_PORTF_DATA_R

= GPIO_PORTF_DATA_R & ~0x02;

; assembly version

LDR R0,=GPIO_PORTF_DATA_R ;pointer to data register

LDR

R1,[R0]

;previous values

BIC

R1,R1,#0x02

;clear bit 1

STR

R0,[R1] ; change output

: How would you change the above program to set the PF3 pin?

: How would you change the above program to toggle the PF2 pin?

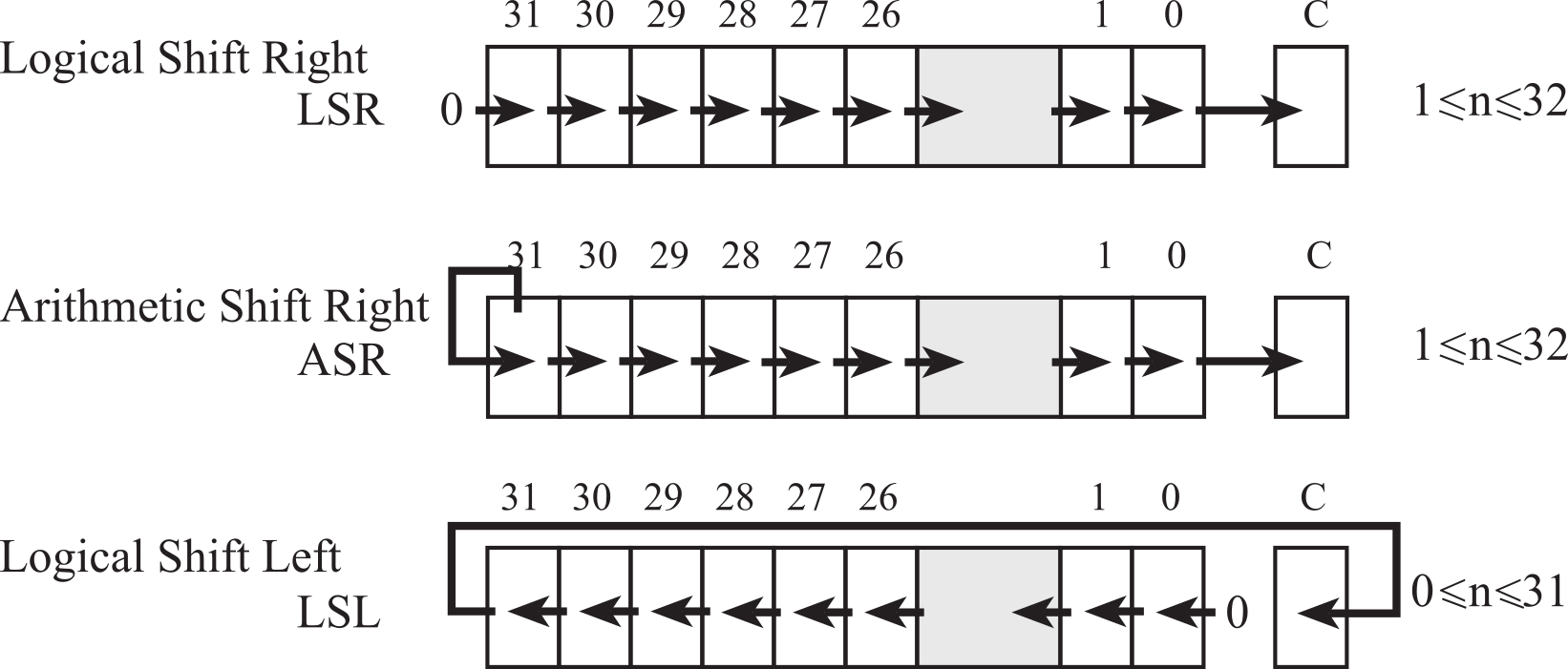

1.7.5. Shift Operations

Like programming in C, the assembly shift instructions take two input parameters and yield one output result. In C, the left shift operator is << and the right shift operator is >>. E.g., to left shift the value in m by n bits and store the result in r we execute: r = m<<n. Similarly, to right shift the value in m by n bits and store result r, we execute: r=m>>n.

Figure 1.7.7. Shift operations move bits to the right or left.

The logical shift right (LSR) is similar to an unsigned divide by 2n, where n is the number of bits shifted. A zero is shifted into the most significant position, and the carry flag will hold the last bit shifted out. The right shift operations do not round. For example, a right shift by 3 bits is similar to divide by 8. However, 15 right-shifted three times (15>>3) is 1, while 15/8 is much closer to 2. In general, the LSR discards bits shifted out, and the UDIV truncates towards 0. Thus, when using UDIV to divide unsigned numbers by a power of 2, UDIV and LSR yield identical results.

The arithmetic shift right (ASR) is similar to a signed divide by 2n. Notice that the sign bit is preserved, and the carry flag will hold the last bit shifted out. This right shift operation also does not round. Again, a right shift by 3 bits is similar to divide by 8. However, -9 right-shifted three times (-9>>3) is -2, while implementing -9 divided by 8 using the SDIV instruction yields -1. In general, the ASR discards bits shifted out, and the SDIV truncates towards 0.

The logical shift left (LSL) operation works for both unsigned and signed multiply by 2n. A zero is shifted into the least significant position, and the carry bit will contain the last bit that was shifted out.

All shift instructions place the result into the destination register Rd. Rm is the register holding the value to be shifted. The number of bits to shift is either in register Rs, or specified as a constant n. If the optional S suffix is specified, the N and Z condition code bits are updated on the result of the operation. The C bit is the carry out after the shift. These shift instructions will leave the V bit unchanged.

Observation: Use logic shift for unsigned numbers and arithmetic shifts for signed numbers.

LSR Rd, Rm, Rs ; logical shift right

Rd=Rm>>Rs (unsigned)

LSR Rd, Rm, #n ; logical shift right

Rd=Rm>>n (unsigned)

ASR Rd, Rm, Rs ; arithmetic shift right

Rd=Rm>>Rs (signed)

ASR Rd, Rm, #n ; arithmetic shift right

Rd=Rm>>n (signed)

LSL Rd, Rm, Rs ; shift left Rd=Rm<<Rs

(signed, unsigned)

LSL Rd, Rm, #n ; shift left Rd=Rm<<n

(signed, unsigned)

: If R0=0xC0123456, what will be the value in R0 after LSR R0,R0,#4 is executed?

: If R0=0xC0123456, what will be the value in R0 after ASR R0,R0,#4 is executed?

: If R0=0xC0123456, what will be the value in R0 after LSL R0,R0,#4 is executed?

1.7.6. Arithmetic Operations

When software executes arithmetic instructions, the operations are performed by digital hardware inside the processor. Even though the design of such logic is complex, we will present a brief introduction, in order to provide a little insight as to how the computer performs arithmetic. It is important to remember that arithmetic operations (addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division) have constraints when performed with finite precision on a processor. An overflow error occurs when the result of an arithmetic operation cannot fit into the finite precision of the register into which the result is to be stored. If the optional S suffix is specified, the N C V and Z condition code bits are updated on the result of the operation.

The immediate value #n can be any 12-bit constant.

When Rd is absent, the result is placed back in Rn.

ADD Rd, Rn, Rm ;Rd = Rn + Rm

ADD Rd, Rn, #n ;Rd = Rn + n

SUB Rd, Rn, Rm ;Rd = Rn - Rm

SUB Rd, Rn, #n ;Rd = Rn - n

CMP Rn, Rm ;Rn - Rm

CMP Rn, #n ;Rn - n

If the optional S suffix is present, addition and subtraction set the condition code bits as shown in the following table. The addition and subtraction instructions work for both signed and unsigned values. As designers, we must know in advance whether we have signed or unsigned numbers. The computer cannot tell from the binary which type it is, so it sets both C and V. Our job as programmers is to look at the C bit if the values are unsigned and look at the V bit if the values are signed.

| Bit | Name | Meaning after addition or subtraction |

| N | Negative | Result is negative |

| Z | Zero | Result is zero |

| V | Overflow | Signed overflow |

| C | Carry | Unsigned overflow |

Table 1.7.2. Condition code bits contain the status of the previous arithmetic operation.

Observation: The carry bit, C, is set after an unsigned addition when the result is incorrect. The carry bit, C, is cleared after an unsigned subtraction when the result is incorrect.

Observation: The overflow bit, V, is set after a signed addition or subtraction when the result is incorrect.

Multiply (MUL) uses 32-bit operands and

produces a 32-bit result. This multiply instructions only save the

bottom 32 bits of the result. They can be used for either signed or

unsigned numbers, but no overflow flags are generated. If the Rd

register is omitted, the Rn register is the destination. If the S suffix

is added to MUL, then the Z and N bits are set according to the

result. The division instructions do not set condition code flags and

will round towards zero if the division does not evenly divide into an

integer quotient

MUL Rd, Rn, Rm ;Rd = Rn * Rm

UDIV Rd, Rn, Rm ;Rd = Rn / Rm (unsigned)

SDIV Rd, Rn, Rm ;Rd = Rn / Rm (signed)

: If one adds an n-bit number to another n-bit number, how total bits are in the sum?

: If one multiplies an n-bit number to an m-bit number, how total bits are in the product?

1.7.7. Branch Instructions

Normally the computer executes one instruction

after another in a linear fashion. In particular, the next instruction

to execute is found immediately following the current instruction. We

use branch instructions to deviate from this straight line path. The

following lists a few of the many branch instructions. The conditional

branching must be preceded by an instruction that sets the condition

code bits.

B label ;unconditional

branch to label

BEQ label ;branch to label if Z=1

BNE label ;branch to label if Z=0

BMI label ;branch to label if N=1

BPL label ;branch to label if N=0

BCS label ;branch to label if C=1

BCC label ;branch to label if C=0

BVS label ;branch to label if V=1

BVC label ;branch to label if V=0

1.8. Designing a NOT gate using a LaunchPad

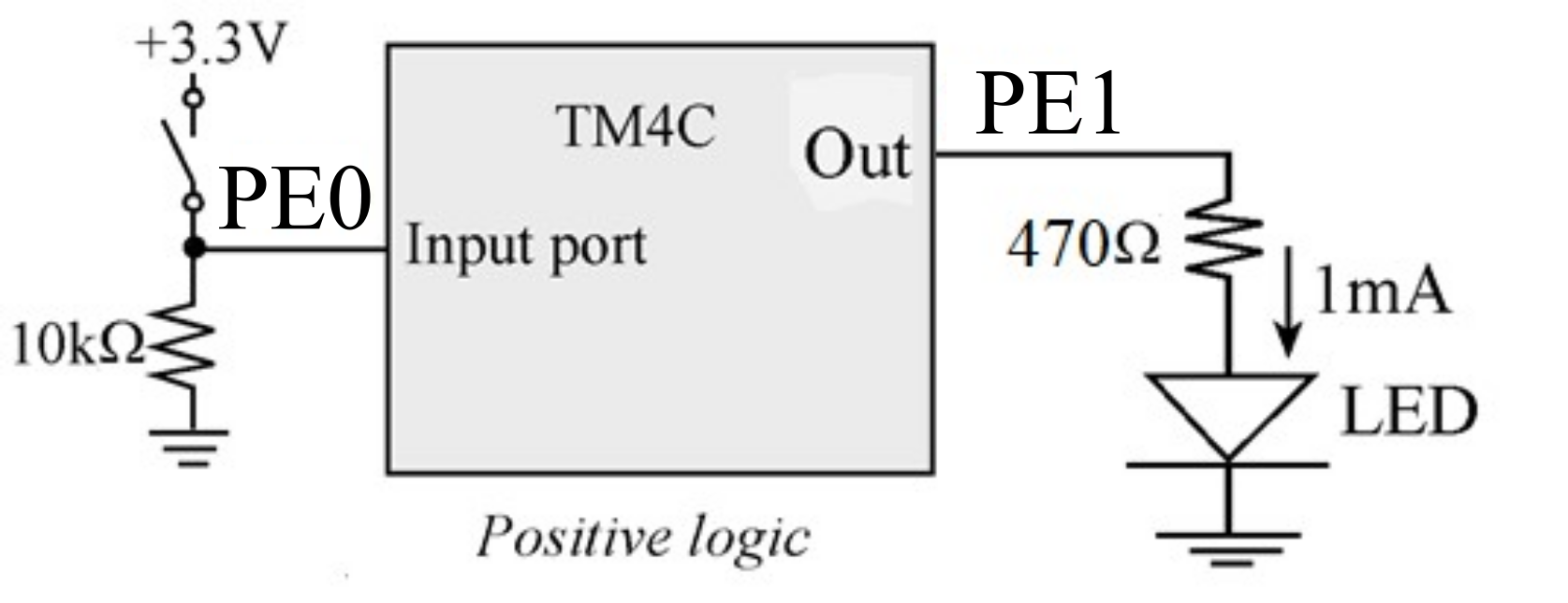

In this section we will combine many of the concepts presented in this chapter to design, build and test a NOT gate using the TM4C123 microcontroller. Any two GPIO pins could have been used, but we chose PE0 as input and PE1 as output. The system will make the PE1 output the logic NOT of the input on PE0. We will test the NOT gate by using a switch on PE0 to generate an input signal, and use an LED on PE1 to visualize the output. Basically if we press the switch, the input on PE0 will be high. The system will make the output on PE1 low, and the LED will be off. Conversely, if we release the switch, the input on PE0 will be low. The system will make the output on PE1 high, and the LED will be on. The details of this circuit will be presented in Chapter 3.

Figure 1.8.1. Circuit to test NOT gate.

To use GPIO pins we must first initialize the port. Program 1.8.1 initializes PE0 as input and PE1 as output. First, we turn on the clock and wait two bus cycles for the clock to stabilize. Then, we set the DIR register to 0x02, making PE1 an output and PE0 an input. Lastly, we set the DEN register to 0x03 to enable both PE1 and PE0. The code in Program 1.8.1 will be executed once at the start of the software, and before we access the data register of Port E

LDR R0,=SYSCTL_RCGCGPIO_R

LDR R1,[R0] ;previous

ORR R1,R1,#0x10 ;bit 4 is clock for E

STR R1,[R0] ;turn on clock for

E

NOP ;wait

NOP ;wait

LDR R0,=GPIO_PORTE_DIR_R

MOV R1,#0x02 ;PE1 output, PE0 input

STR R1,[R0]

LDR R0,=GPIO_PORTE_DEN_R

MOV R1,#0x03 ;enable PE1,PE0

STR R1,[R0]

Program 1.8.1. Initialization of Port E, making PE1 an output and PE0 an input.

Effective testing starts with the simplest component. We begin by connecting the LED to PE1 and writing test code to see if the software can control the LED state. The assembly code in Program 1.8.2 will toggle the output on PE1. R0 points to the data register for Port E. R1 contains the value of Port E, which we read-toggle-write. R2 contains a large number, and is used to create a long delay, so we can see the LED flash with our eyes. The accesses to R3 will slow down the wait loop. The SUBS instruction decrements the R2 counter and sets the Z bit when the counter reaches 0. The BNE instruction will branch if the Z bit is not set (R2 is not zero). The B loop instruction is an unconditional branch so the code is repeated over and over.

LDR

R0,=GPIO_PORTE_DATA_R

loop

LDR R1,[R0] ;read all of

PortE

EOR R1,R1,#0x02 ;toggle bit 1

STR R1,[R0] ;output to

PortE

LDR R2,=1000000

wait

MOV R3,#1000 ;dummy operation

MOV R3,#2000 ;dummy operation

MOV R3,#3000 ;dummy operation

MOV R3,#4000 ;dummy operation

SUBS R2,R2,#1

BNE wait

B loop

Program 1.8.2. Toggle the PE1 output.

The assembly code in Program 1.8.3 will create a NOT gate, using PE0 as input and PE1 as output. First, we read all of Port E. We select just bit 0 using the AND instruction with mask #1. Next, we toggle bit 0 using the EOR instruction to implement the NOT operation. We use the LSL instruction to move the information in bit 0 into the bit 1 location. Lastly we output to Port E, making the pin PE1 the logical NOT of the input from PE0.

LDR

R0,=GPIO_PORTE_DATA_R

loop

LDR R1,[R0] ;Read Port E

AND R1,R1,#1 ;mask, select PE0

EOR R1,R1,#1 ;NOT

LSL R1,R1,#1 ;move to bit 1

STR R1,[R0] ;write Port E, sets PE1

B loop

Program 1.8.3. A NOT gate with PE0 as input and PE1 as output.

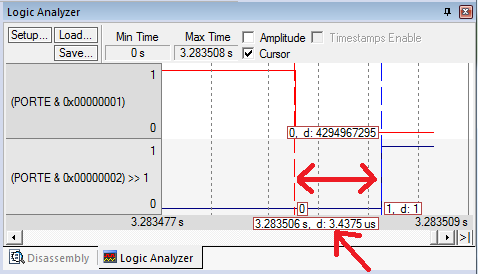

Finally, we connect the switch to PE0 and single step through the code. We step through the loop with the switch not pressed to see the LED come on, and with the switch pressed to see the LED go off. If we connect a logic analyzer to PE1 and PE0, we test dynamic behavior of the system. Running in simulation with a bus clock of 16 MHz, we see it takes 3.4us for a change in input to propagate to the output. This delay, of course, will depend on which of six instructions in the loop are being executed when the input is changed. The worst case would be to change during the AND instruction because it would have to execute 10 instructions until the output changed: AND-EOR-LSL-STR-B-LDR-AND-EOR-LSL-STR.

Figure 1.8.2. Simulated logic analyzer signals measuring propagation delay of the NOT gate.

Reprinted with approval from Introduction to Embedded Systems, 2022, ISBN: 978-1537105727

Embedded Systems - Shape the World by Jonathan Valvano and Ramesh Yerraballi is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at http://users.ece.utexas.edu/~valvano/arm/outline1.htm.